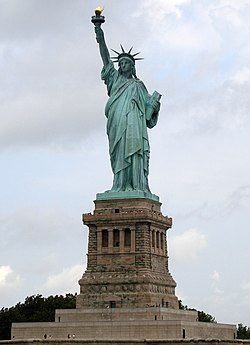

Statue of Liberty

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Liberty Island Manhattan, New York City, New York,[1] U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°41′21″N 74°2′40″WCoordinates: 40°41′21″N 74°2′40″W |

| Height |

|

| Dedicated | October 28, 1886 |

| Restored | 1938, 1984–1986, 2011–2012 |

| Sculptor | Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi |

| Visitors | 3.2 million (in 2009)[2] |

| Governing body | U.S. National Park Service |

| Website | Statue of Liberty National Monument |

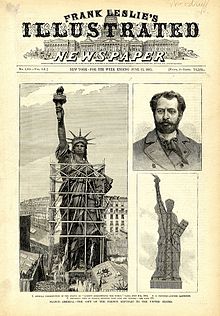

Construction in France

On his return to Paris in 1877, Bartholdi concentrated on completing the head, which was exhibited at the 1878 Paris World's Fair. Fundraising continued, with models of the statue put on sale. Tickets to view the construction activity at the Gaget, Gauthier & Co. workshop were also offered.[50] The French government authorized a lottery; among the prizes were valuable silver plate and a terracotta model of the statue. By the end of 1879, about 250,000 francs had been raised.[51]

The head and arm had been built with assistance from Viollet-le-Duc, who fell ill in 1879. He soon died, leaving no indication of how he intended to transition from the copper skin to his proposed masonry pier.[52]The following year, Bartholdi was able to obtain the services of the innovative designer and builder Gustave Eiffel.[50] Eiffel and his structural engineer, Maurice Koechlin, decided to abandon the pier and instead build an iron truss tower. Eiffel opted not to use a completely rigid structure, which would force stresses to accumulate in the skin and lead eventually to cracking. A secondary skeleton was attached to the center pylon, then, to enable the statue to move slightly in the winds of New York Harbor and as the metal expanded on hot summer days, he loosely connected the support structure to the skin using flat iron bars[28] which culminated in a mesh of metal straps, known as "saddles", that were riveted to the skin, providing firm support. In a labor-intensive process, each saddle had to be crafted individually.[53][54] To prevent galvanic corrosion between the copper skin and the iron support structure, Eiffel insulated the skin with asbestos impregnated with shellac.[55]

Eiffel's design made the statue one of the earliest examples of curtain wallconstruction, in which the exterior of the structure is not load bearing, but is instead supported by an interior framework. He included two interior spiral staircases, to make it easier for visitors to reach the observation point in the crown.[56] Access to an observation platform surrounding the torch was also provided, but the narrowness of the arm allowed for only a single ladder, 40 feet (12 m) long.[57] As the pylon tower arose, Eiffel and Bartholdi coordinated their work carefully so that completed segments of skin would fit exactly on the support structure.[58] The components of the pylon tower were built in the Eiffel factory in the nearby Parisian suburb of Levallois-Perret.[59]

The change in structural material from masonry to iron allowed Bartholdi to change his plans for the statue's assembly. He had originally expected to assemble the skin on-site as the masonry pier was built; instead he decided to build the statue in France and have it disassembled and transported to the United States for reassembly in place on Bedloe's Island.[60]

In a symbolic act, the first rivet placed into the skin, fixing a copper plate onto the statue's big toe, was driven by United States Ambassador to France Levi P. Morton.[61] The skin was not, however, crafted in exact sequence from low to high; work proceeded on a number of segments simultaneously in a manner often confusing to visitors.[62] Some work was performed by contractors—one of the fingers was made to Bartholdi's exacting specifications by a coppersmith in the southern French town of Montauban.[63] By 1882, the statue was complete up to the waist, an event Barthodi celebrated by inviting reporters to lunch on a platform built within the statue.[64] Laboulaye died in 1883. He was succeeded as chairman of the French committee by Ferdinand de Lesseps, builder of the Suez Canal. The completed statue was formally presented to Ambassador Morton at a ceremony in Paris on July 4, 1884, and de Lesseps announced that the French government had agreed to pay for its transport to New York.[65] The statue remained intact in Paris pending sufficient progress on the pedestal; by January 1885, this had occurred and the statue was disassembled and crated for its ocean voyage.[66]

The committees in the United States faced great difficulties in obtaining funds for the construction of the pedestal. The Panic of 1873 had led to an economic depression that persisted through much of the decade. The Liberty statue project was not the only such undertaking that had difficulty raising money: construction of the obelisk later known as the Washington Monumentsometimes stalled for years; it would ultimately take over three-and-a-half decades to complete.[67] There was criticism both of Bartholdi's statue and of the fact that the gift required Americans to foot the bill for the pedestal. In the years following the Civil War, most Americans preferred realistic artworks depicting heroes and events from the nation's history, rather than allegorical works like the Liberty statue.[67] There was also a feeling that Americans should design American public works—the selection of Italian-born Constantino Brumidi to decorate the Capitol had provoked intense criticism, even though he was a naturalized U.S. citizen.[68] Harper's Weekly declared its wish that "M. Bartholdi and our French cousins had 'gone the whole figure' while they were about it, and given us statue and pedestal at once."[69] The New York Times stated that "no true patriot can countenance any such expenditures for bronze females in the present state of our finances."[70] Faced with these criticisms, the American committees took little action for several years.[70]

Design

The foundation of Bartholdi's statue was to be laid inside Fort Wood, a disused army base on Bedloe's Island constructed between 1807 and 1811. Since 1823, it had rarely been used, though during the Civil War, it had served as a recruiting station.[71]The fortifications of the structure were in the shape of an eleven-point star. The statue's foundation and pedestal were aligned so that it would face southeast, greeting ships entering the harbor from the Atlantic Ocean.[72] In 1881, the New York committee commissioned Richard Morris Hunt to design the pedestal. Within months, Hunt submitted a detailed plan, indicating that he expected construction to take about nine months.[73] He proposed a pedestal 114 feet (35 m) in height; faced with money problems, the committee reduced that to 89 feet (27 m).[74]

Hunt's pedestal design contains elements of classical architecture, including Doricportals, as well as some elements influenced by Aztec architecture.[28] The large mass is fragmented with architectural detail, in order to focus attention on the statue.[74] In form, it is a truncated pyramid, 62 feet (19 m) square at the base and 39.4 feet (12.0 m) at the top. The four sides are identical in appearance. Above the door on each side, there are ten disks upon which Bartholdi proposed to place the coats of arms of the states (between 1876 and 1889, there were 38 U.S. states), although this was not done. Above that, a balcony was placed on each side, framed by pillars. Bartholdi placed an observation platform near the top of the pedestal, above which the statue itself rises.[75] According to author Louis Auchincloss, the pedestal "craggily evokes the power of an ancient Europe over which rises the dominating figure of the Statue of Liberty".[74] The committee hired former army General Charles Pomeroy Stone to oversee the construction work.[76] Construction on the 15-foot-deep (4.6 m) foundation began in 1883, and the pedestal's cornerstone was laid in 1884.[73] In Hunt's original conception, the pedestal was to have been made of solid granite. Financial concerns again forced him to revise his plans; the final design called for poured concrete walls, up to 20 feet (6.1 m) thick, faced with granite blocks.[77][78] This Stony Creek granite came from the Beattie Quarry in Branford, Connecticut.[79] The concrete mass was the largest poured to that time.[78]

Norwegian immigrant civil engineer Joachim Goschen Giæver designed the structural framework for the Statue of Liberty. His work involved design computations, detailed fabrication and construction drawings, and oversight of construction. In completing his engineering for the statue's frame, Giæver worked from drawings and sketches produced by Gustave Eiffel.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.